da dacemagazine.comBrits on BroadwayEmily Macel Peter Darling puts on a pair of red leather boxing gloves and spars

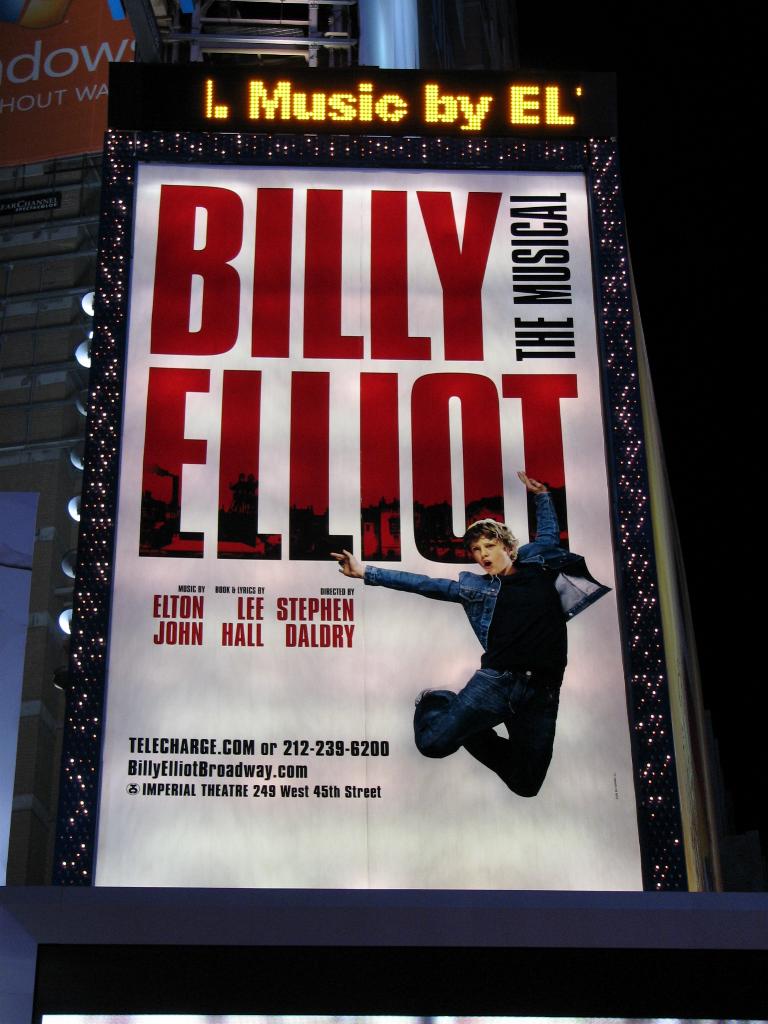

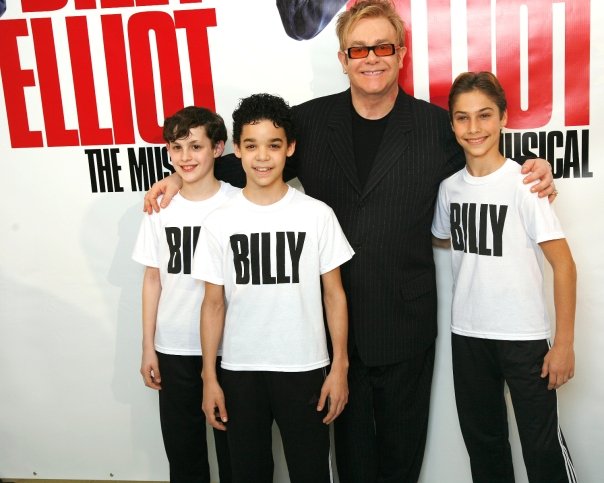

with himself in the mirror of a dance studio above Times Square. He

looks more like an athlete—a boxer even—than a dancer. But this month,

it’s Darling’s choreography that packs a punch on Broadway. Haydn Gwynne, who plays the brassy ballet teacher Mrs. Wilkinson, and Trent Kowalik, one of the three Billys cast for the American production, have both performed their roles in the West End. In rehearsal, Darling shows them how to throw uppercuts at each other, as they work on a number called “Born to Boogie” that will get additional choreography. Why tweak—if the musical’s not broke, why fix it? “The intention is to try and tell the story better,” Darling says. Gwynne says, “It seems cheeky bringing a British musical to Broadway where the art form was created. While it is a very British piece, I hope that people appreciate its appeal. They have an idea of what it’s like based on the movie, but I think they’ll find they’re getting more than they bargained for.” Gwynne and Kowalik work on a choreographed boxing battle, in which Mrs. Wilkinson tries to trick Billy into dancing. “I think you’re tempting him,” Darling tells Gwynne. “You’re saying I don’t care if you join in, but I know you will.” The movements are simple, at times pedestrian. Darling has a childlike quality while he creates movement. When Kowalik attempts to play air guitar as part of the choreography, Darling jumps in to demonstrate. He shows Kowalik how to strum, how to play invisible frets, and how to look like a rock star while leaping across the stage and wailing on the imaginary instrument. When asked if he sees himself in Billy, Darling says, “No, but other people do.” Darling brings enormous focus when he works. The London native has performing in his genes. “My father was in variety shows and I used to watch them as a kid. I knew all the routines.”At an early age, he began taking ballet, jazz, and tap at a performing arts school. “Then I stopped and decided I was going to have nothing to do with dance. I switched to training as an actor.” He acted for 10 years, but his movement training led him to DV8, the physical theater and dance company run by Lloyd Newson (“Dance Matters,” Oct.). “It was a lot of physical work. Newson sets you tasks to complete and shape.” Like Newson, Darling thrives on collaboration. “I don’t believe in a vertical system,” he says. “I think every single person in the room is as creative and intelligent as the other. The more one can not lead through domination, the better.” When Darling choreographed the London musical Oh! What a Lovely War, Stephen Daldry, who was slated to direct Billy Elliot, came to see the production. He thought Darling’s choreography was a fit for the film, and left the script at the stage door for his consideration. Darling gladly accepted. The plot of the movie has a few layers. Aside from Billy realizing he wants to become a dancer, his best friend Michael must come to terms with his own homosexuality. Billy’s family has been drawn into the miners strike: Billy’s father and brother chose different sides of the picket line. Though there are energetic dance scenes in the movie, the transfer to musical theater takes that focus on dance and multiplies it by a hundred. “You can’t cut away and cheat on the stage because you’re always in long shot,” says Darling. “The child has to really be able to do a double pirouette. The story’s broader focus gave me a chance to open up a wider spectrum of dance styles. Ballet sits alongside tap, which sits alongside physical theater, which sits alongside pedestrian movement.” He felt that putting the story onstage let him move outside a balletic vocabulary, and mix in modern and contemporary styles. The search for who would play Billy on Broadway was intense. More than 1,500 boys auditioned, and the casting crew scaled it down to those who were proficient in ballet, tap, and contemporary dance. (Since Billys inevitably outgrow the role, Billy wannabees should go to www.bebilly.com.) Though the movie has a few rhythmic dance sequences, tap becomes crucial in the musical version. Darling built up these sections because clogging has long been part of the miners’ world in Britain. “It’s not the tap that you’d see very underneath you, very syncopated,” he says. “It’s much more like step dancing with jumps and strange clogging moves.” Darling feels the hardest part of setting the musical on a new cast is helping them connect with the story and the movement. “I passionately believe that no movement is neutral; all movement is expressive,” he says. Watching the Billys blossom has been the biggest reward. “The most enjoyable part are the boys in terms of their development and achievement. You want to really help them on that journey.” The production, which began previews in October and opens November 13 at the Imperial Theater, has a cast of 51. The Billys, though young, come with impressive resumés. David Alvarez, 14, is studying on scholarship at American Ballet Theatre’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School; Kiril Kulish, 14, won the Grand Prix in the junior age division at the Youth America Grand Prix in 2007; and Kowalik, 13, was the youngest American male to win the World Irish Dancing Championship at age 11. A New York native, Kowalik blogs on his website regularly about his experiences with the musical (trentkowalik.com). Stephen Hanna is taking a leave from New York City Ballet to play the role of an older Billy in the dream sequence. He and the young Billy perform a pas de deux that uses a flying apparatus which has Billy soaring across the stage. “I think the biggest difference from dancing with NYCB is that there is so much depth behind the story,” he says. “There’s a lot of things left up to us to decide, but we have motivation as to how to do that.” Darling hopes that the musical will make audiences question why ballet for boys remains taboo. “Why is it that we on one hand are happy enough for people to break dance, but we’re not happy for a boy to suddenly go into an arabesque?” Darling’s proudest accomplishment has been the degree to which the movie and musical have broken down that stereotype. “The Royal Ballet School now has many more boys in their annual auditions,” he says. “And they attribute it to the success of Billy Elliot. I think if the show hits a nerve, it can give boys who want to be ballet dancers something they can say—‘I want to be like Billy Elliot’—and it won’t seem like something unacceptable anymore.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Billy Elliot | Lee Hall |